The short answer is the Federal Trade Commission announced it is banning non-competes for the majority of workers retroactively, and all workers proactively. But it is unclear if the courts will allow the FTC to implement its ban.

Early last year, we discussed the FTC’s initial proposed rule to ban non-compete clauses. After allowing the public to provide comments, the FTC provided notice of its final rule on April 23, 2024. The FTC’s final rule is thorough, and the FTC provided 570 pages of material to support its final rule. The rule is not effective for 120 days (or until August 21, 2024).

But the day after the FTC announced the final rule, on April 24, 2024, the US. Chamber of Commerce filed a lawsuit in a Texas federal court to challenge the FTC’s authority to implement the rule, as did global tax services firm Ryan LLC. Other interest groups may file lawsuits as well.

If the ban becomes effective, businesses will have to provide notice to employees regarding their existing non-competes, and businesses will have to modify their agreements moving forward. In the meantime, businesses should monitor the legal challenges to the ban to determine whether a court will enter an injunction before the rule becomes effective.

What Is a Non-Compete?

A non-compete agreement or a non-compete clause in a larger employment agreement seeks to prevent an employee from working for a competitor for a specific time period in a specific geographic location. Companies include non-compete clauses in various types of agreements, including in traditional employment agreements, in severance agreements, in equity agreements, or in agreements governing a company’s purchase of another business. Depending on which document in which the non-compete is contained, courts may use different tests to determine whether the non-compete is enforceable.

Separate from a non-compete, a non-solicit seeks to prohibit an employee from soliciting the former employer’s clients or other employees. And a confidentiality clause or non-disclosure agreement seeks to prohibit the disclosure of confidential information.

There is no national law or federal law governing non-compete clauses. Instead, every state has its own non-compete law, and the laws are vastly different. Some states ban non-competes, other states have nuanced requirements to enforce non-competes, and some states apply a hybrid approach (banning non-competes for certain workers, and allowing non-competes if the clauses meet specific requirements).

In states where a non-compete can be enforceable, courts closely scrutinize non-competes because these clauses restrain trade and impact employee mobility. And in addition to these clauses, there are state and federal law protections for a company’s trade secrets.

What Did the FTC Do?

In simple terms, the FTC is banning non-compete clauses retroactively and proactively for all workers; one exception is for existing non-compete clauses concerning senior executives. The FTC is implementing “a comprehensive ban on new non-competes with all workers.” And “[f]or workers who are not senior executives, existing non-competes are no longer enforceable after the rule’s effective date.” Employers will have to provide notice to workers that the such non-competes are not enforceable. And the final rule pre-empts state laws that conflict with the final rule.

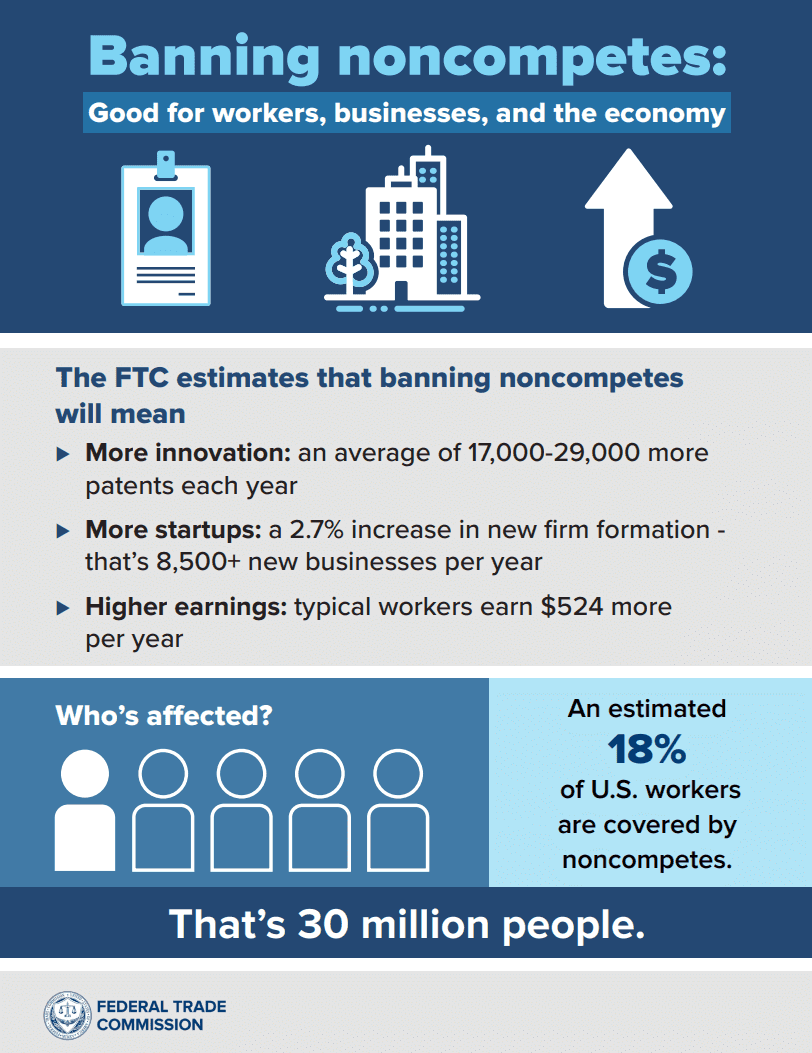

The purpose of the FTC’s rule is “to promote competition by banning noncompetes nationwide, protecting the fundamental freedom of workers to change jobs, increasing innovation, and fostering new business formation.” The FTC anticipates that banning non-competes will promote business and wage growth. In its initial notice, the FTC included the graphic reproduced on this page.

For the past few years, the FTC researched the impact of non-competes. The FTC held hearings, offered a public workshop, sought public comments, and initiated investigations. After announcing its proposed rule last year, the FTC received over 26,000 public comments. Information from these various efforts, including some comments, was included in the voluminous publication of the final rule.

Based on its research, the FTC estimates that about one in five American workers—approximately 30 million people—are subject to a non-compete. And employers across industries use non-competes. As one example, the FTC indicated that “a survey of independent hair salon owners finds that 30% of hair stylists worked under a non-compete in 2015.” The FTC’s research further indicates that employers use non-competes even when the clause may not be enforceable.

Ultimately, the FTC believes that non-competes harm competitive conditions in labor markets, and harm competitive conditions in product and service markets: the clauses restrict worker mobility and decrease wages, and they harm consumers by creating obstacles for new businesses.

The FTC explained that certain another types of agreements, such as a non-disclose agreement or a non-solicitation agreement (which seek to prohibit the solicitation of customers or employees) can satisfy the definition of a “non-compete clause” when the clauses function to prevent a worker from seeking or accepting other work or starting a business.

The final rule does not impact non-competes that restrict work solely overseas or outside the U.S.

How Does the Final Rule Differ from the Proposed Rule?

One major difference between the FTC’s proposed rule and its final rule is a carve-out for senior executives. Existing non-competes with “senior executives” can remain in place, but moving forward, the FTC is banning non-competes with all workers—senior executives or otherwise.

The final rule defines “senior executive” to include both an earning threshold and a job duties test. Under the final rule, a “senior executive” must make more than $151,164 and must be in a “policy-making position,” which means a president, a CEO, or the equivalent, and who makes policy decisions that control significant aspects of a business entity or a common enterprise. The FTC estimated that approximately 0.75% of all workers are “senior executives.”

The rule also does not apply to non-competes entered into as a result of the sale of a business or to matters that will have accrued before the effective date of the ban. There are also some changes to definitions between the final rule and the proposed rule.

What Are the Legal Challenges?

As part of its final rule, the FTC attempted to address the likely legal challenges, which include:

- Whether the FTC has authority under the FTC Act to promulgate rules regarding unfair competition

- The major questions doctrine, or whether Congress meant to confer the authority to the FTC for such an impactful matter

- Whether Congress violated the non-delegation doctrine by providing the FTC with such authority

- Whether the final rule violates the Commerce Clause by regulating local commerce

- Implications of the 10th Amendment of the Constitution

- Implications of the Constitution’s Contracts Clause

- Whether the final rule is too vague

- Compliance with the Administrative Procedure Act

- Jurisdiction over non-profit organizations

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Ryan LLC filed their lawsuits in federal courts in Texas to challenge the rule, arguing that the rule violates the Administrative Procedure Act in various ways.

What Happens Next?

The final rule is the culmination of a trend from the past dozen years of increased scrutiny of non-compete clauses. States continue to pass laws to make it harder to enforce a non-compete. The general public is much more knowledgeable about these clauses today than in 2012 (anecdotally, I’ve received a lot of messages from friends and family about the FTC’s ruling). And businesses may become less inclined to require employees to sign broad covenants.

For the short term, businesses should monitor pending legal challenges. A legal challenge could result in a temporary injunction to allow the courts to determine if the rule is legally enforceable. If the rule is effective, businesses will have to provide notice to their employees regarding the final rule, and businesses will also have to update their agreements for new employees.

Regardless of whether the FTC can enforce the final rule, the FTC’s thorough research will impel state legislatures (and potentially Congress) to continue to pass laws, will influence courts and judges on questions of enforceability, and will affect businesses.